Kamukunji mental health circle where men find a safe space to speak out

Statistics from the Kenya Red Cross show that Kenyan men are four times more likely to commit suicide than women, and they account for 80 per cent of all suicides.

When 31-year-old Kevin Yahuma lost Sh700,000 in 2017 after a bad investment, he went into depression and was suicidal for two years. He was then working in Qatar and had met a Kenyan “friend” online with whom he became acquaintances for over a year.

“I felt like I knew him very well. We had planned to invest in potato farming, and I sent him Sh700,000 to start the project,” he says.

More To Read

- Violence is a normal part of life for many young children: Study traces the mental health impacts

- When birth brings heartbreak: Mothers share their stories of children with deformities

- Explainer: As mental health challenges rise, here is what you need to know about antidepressants

- Mental health advocates call for community-based support as economic strain deepens

- How to talk to your kids about mental health

- Doctors Without Borders sounds alarm as mentally ill detained in South Sudan prisons

But when he returned to Kenya, he could not find him. His “friend” had blocked him from all his social sites. Yahuma even engaged the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, but they were unable to trace the culprit.

The loss was unbearable to him. He felt bad that after all his efforts in a foreign country seeking to offer his mother a better life, he would not be able to do so.

“I started becoming violent towards my family and my girlfriend. I found temporal relief in alcohol and soon became an alcoholic and promiscuous. The little savings I had were lost in alcoholism,” he says.

While his friends became concerned about his behaviour change, he did not think he was depressed. However, he gradually lost interest in life, and nothing seemed exciting. He got to a point where he wished he could run mad. This was followed by suicidal thoughts.

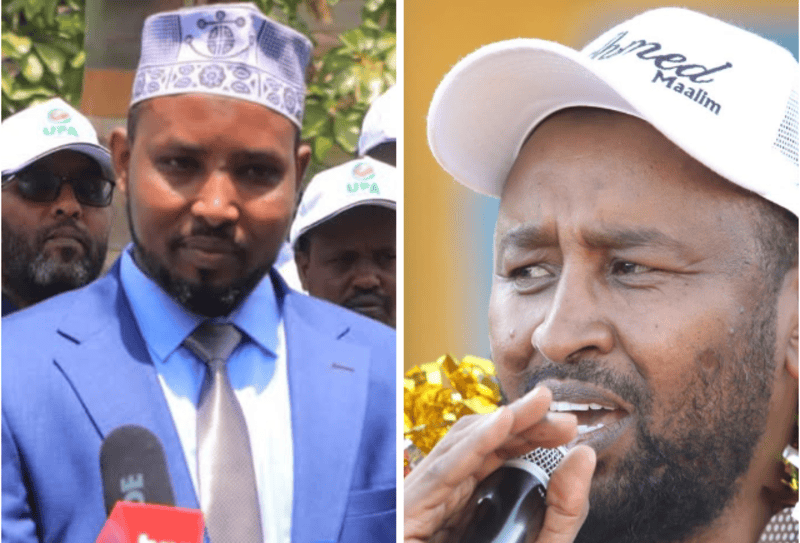

It was at this point that one of his friends, 45-year-old Mohammed Kioko, a mental health advocate, persuaded him to seek help from the Kamukunji Mental Health Circle.

Kevin was lucky to have gotten help. Like him, many men suffer mental health challenges in silence and only seek help when it is too late.

The age-old stereotype that men should always act strong and stoic and “man up” whenever they are faced with challenges is leading many to mental health breakdowns.

Kamukunji Historical Park has green area where you can relax. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Kamukunji Historical Park has green area where you can relax. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Statistics from the Kenya Red Cross show that Kenyan men are four times more likely to commit suicide than women, and they account for 80 per cent of all suicides. It also shows that one in 10 men experiences depression, yet only half receive treatment.

This is partly why June has been designated as men’s mental health awareness month. This year’s theme is “Be the source for better health: Improving men’s health outcomes through our cultures, communities, and connections”.

“Men are dying in silence because when they tell their spouses what they are going through, they tell them to stop ‘venting like women’ and act like men,” Yahuma says.

He started his healing journey through self-acceptance.

“I came to terms with the fact that I had lost my hard-earned money and I would never recover it. I also accepted that I was indeed depressed, and the behaviour I was exhibiting was a result of this,” he says.

He realised this after group counselling sessions at the mental health circle, a programme run by the Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions (KECC) located at the Kamukunji Historical Park in Nairobi. His friend Mohammed, himself a community health promoter in Shauri Moyo and a volunteer at the chief’s office, introduced him to the group.

He says Mohammed not only introduced him to the mental health circle but also followed up on his progress.

“He would send my sister to look for me or ask my mother where I was if I missed sessions. During the sessions, the group would come up with a topic that allowed some to vent, others to give their point of view, and others to listen. In time, I established that it was a safe space for men, and our private struggles were validated. I also made friends who understood my struggles and did not judge me,” says Yahuma.

He says that he came to learn that some men had tried to fight depression by watching “how to battle depression” videos on YouTube since they did not have someone to talk to.

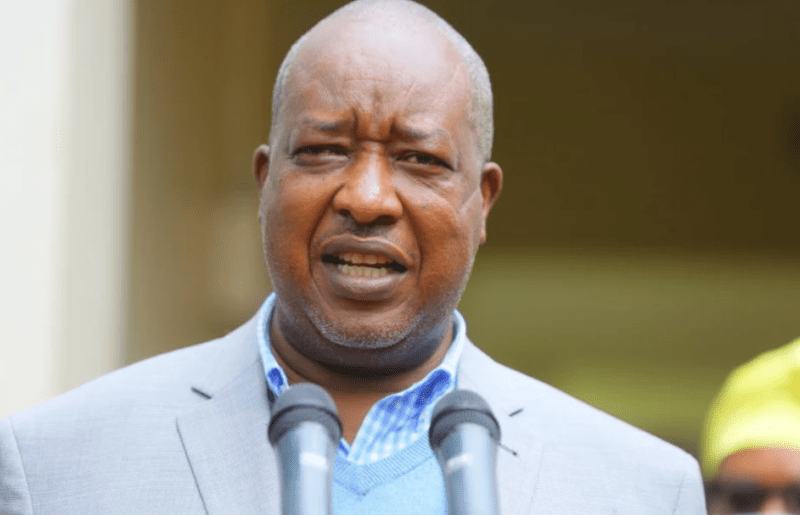

KECC chairman Josephat Karomi says that while ego is important to a man, it does not always mean bottling up feelings to maintain it. The Kamukunji Mental Health Circle is showing men that struggling does not mean they are weak.

“We started regenerating part of the Kamukunji Historical Park that was bushy at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The restrictions that had been imposed on movement meant that people did not have a lot of options for a green area where they could relax or for children to play, and the park presented the best place to develop this,” says Karomi.

Karomi and KECC vice chairperson Fatuma Wanjiru say it was at this time that they realised men were struggling.

Fatuma Wanjiru, the vice-chair lady of Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions at the Kamukunji Historical Park. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Fatuma Wanjiru, the vice-chair lady of Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions at the Kamukunji Historical Park. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)Fatuma Wanjiru, the Vice chairlady of Kamukunji Environmental Conservation Champions at the Historic Kamukunji park 2

“Many people lost their jobs. At times we would find smartly dressed young men who would come to the park just to sleep and would not talk to anyone. We had been trained on trauma healing before, and we identified signs of depression in some of those that came to the park, and this is where the idea of the mental health circle came up,” says Fatuma.

Fatuma says the idea of forming the circle was to help both men and women, but it was rare to see women at the park.

At the mental health circle, men come together and sit in a circle. A KECC representative or one of the men comes up with a topic for discussion. It could be about mental health or the political happenings in the country. This helps the men lose their inhibitions, and, with time, they begin opening up, and healing ultimately happens.

“The circle is open to anyone, and for those who are new to it, they prefer to sit and listen as others speak. With time, after they establish that it is a safe space and they are not judged for what they are going through, they begin opening up, and healing starts,” says Karomi.

Karom is now a mental health advocate, youth leader in his church, and secretary of the Decoder Youth Group, one of the community-based organisations that work with KECC. He has also established a self-help group where members contribute money weekly and assist each other in buying household items. His main source of income is from online writing and marketing.

Mohammed Kioko is also a beneficiary of the circle and says that men, just like women, have challenging situations.

“Men come to the circle with a variety of challenges, though financial and relationship problems are the major ones,” says Mohammed.

He says that some men are unable to meet their families' financial needs and opt to run away. Most will go to sleep at the park to while away their problems.

“Some are watchmen, while others work at night at the Marikiti market offloading foodstuffs, and so they sleep at the park during the day. Some of the offloaders and watchmen, especially those whose families are upcountry, do not rent a house in Nairobi and thus spend their day sleeping at the park,” says Mohammed.

He says that the park has been a welcome escape for many, and there have been positive outcomes from this engagement.

The park also hosts a leisure corner, a base just for men where they sometimes play games such as ludo.

Fatuma says that, unlike women who open up freely, it is more challenging for men to open up, making mental healing for some a longer process. However, talking things out in a group setting helps, as the more reserved ones usually approach members of KECC individually whenever they have something bothering them or they just want to talk.

“People who come to the park are from varied socioeconomic backgrounds, and they just want a place to relax, sleep, and forget their problems, even if just momentarily. This then becomes their safe space, where they meet a loving community that does not judge them based on their outward appearance and embraces them as they are. Isolation usually makes the problem seem bigger, and being in such a community and talking transforms their lives for the better,” she says.

Joseph Nginya, a consulting psychologist at Eden Consultants, says the toxic “man up” stereotype is pushing many to seek “manly” escapes such as alcohol, substance abuse and violence.

“This cultural norm has resulted in men who cannot admit when they are struggling and has resulted in the normalisation of terms such as ‘mwanaume ni kujikaza kijeshi’ or ‘kaa strong kimwanaume’ (a man must always stay strong). There are other derogatory ones, such as ‘wacha umama’, which equates the man to ‘behaving like a woman’, and this prevents many from seeking help.”

Kamukunji Historical Park's children's play area. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Kamukunji Historical Park's children's play area. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Nginya says the recent incident of a policeman killing a magistrate is one of many cases of men needing help but finding none.

He says that post-Covid-19, the state of mental health among men is significant and a growing concern.

“The number of men I see is rising significantly in all age groups. While those who are seeking help are the professionals who can pay for the support, those that cannot afford it are seeking alternative ways, which are only aggravating their situation as they are only numbing them for a while,” he says.

He says that financial and relationship issues are contributing greatly to men’s mental health decline.

“Twenty-five per cent of outpatients in Kenya are presenting with a form of mental illness. Seven out of every 10 cases have been linked to men. This results in women outliving men. For married men, for instance, their women are outliving them by 25 to 30 years,” he says.

At the same time, Nginya says the struggles are different in the different age brackets but are all a desperate cry for help.

For teenage boys in their early 20s, their struggle is from high expectations by their parents and society to do well in school, unemployment, and economic strain that is making them feel inadequate, thus seeking alternative ways of escape such as crime, alcoholism, and relationships with older women for financial gain, and identity crisis where they are trying to conform to masculine stereotypes.

Those between the ages of 30 to 50 struggle to meet the financial needs of their families and to maintain a certain social status. They also face job insecurity and are trying to integrate a work-life balance. Many are struggling with balancing work demands and being a present father and husband.

International organisations are experiencing divorces, especially when young men have to work away from home for a while. They are unable to balance family and the demands of the flesh, leading to affairs that result in family disintegration.

This age group also experiences chronic health conditions as the fast-paced lifestyle results in a lack of adequate time to exercise and eat healthy food.

For those over 60 years old, retirement leads to identity loss. Those who were workaholics and did not nurture good relationships with their spouses, children, and family members, become lonely, and depression sets in.

They also suffer from declining health, and some are still reluctant to seek medical help as they still have the masculine stereotype that seeking help is for women, until the situation is dire.

Part of the transformed area of the Kamukunji Historical Park. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Part of the transformed area of the Kamukunji Historical Park. (Photo: Immaculate Wairimu)

Top Stories Today